Foodprints of meals: Focus on organic

What is the environmental impact of the various meals that we eat? Are meals cooked from organic ingredients better for the environment than ingredients from conventional produce? What impact categories are relevant to measure environmental impact of meals anyway?

These are some of the questions that were buzzing in my head as I was attending the Organic Foodprint workshop held in early November 2016 in Zurich, Switzerland. Organised by the Zurich-based company Eaternity, the workshop gathered some leading experts in the field to pick their brains on finding the answers to the questions posed above – with a specific focus on organic produce. Thanks to funding from the WFSC Ambassadors Program (that covered my travel and accommodation) I was very happy to be among the experts in the room.

In search of the answers

I’ve come to Zurich to specifically investigate how organic produce would perform in quantitative assessment of environmental impact of meals (or ‘foodprint’ for short here). Quantitative impact assessment is predominantly done by using a method in which each stage of the production is taken into account and the overall impacts in various impact categories are evaluated – a so called ‘Life Cycle Assessment’ (LCA). I was wondering what the most up-to-date research approaches within this method are and whether the environmental benefits of organic production can be captured by it quantitatively.

This was of interest in relation to my current research project at Charles University in Prague that aims to develop an educational tool for the general public to learn about the environmental and nutritional impacts of food consumption. This might seem relatively simple to do, but due to the complexity of the food system, there are many challenges in developing such a tool and presenting it publicly that make it a rather tricky task.

Learning about the developments in the meaning of “Organic” as part of the Organic Foodprint workshop (photo: Dana Kapitulčinová)

I was therefore very excited to learn about the work of Eaternity who have for a number of years worked on the concept of “climate-friendly meals” and the opportunity to participate in their Organic Foodprint workshop that aimed at exactly my question regarding organic food and environmental assessment. During the event, the Eaternity team presented their research activities along with their university research partner, followed by a series of discussions together with all the other experts attending (there were some 35 people from at least five countries!). We were led into some very creative but at the same time expert-knowledge-requiring tasks to share our experience and express our views on some of the questions posed above.

Found the answers?

The workshop was very lively and enriching and covered many important topics, including those that sparked a debate on somewhat controversial topics (such as meat-free diets or insect eating). The take away answers from the discussions that I took home from Zurich were the following:

What is the environmental impact of the various meals that we eat?

Taking into account carbon footprint (as one of the most commonly used indicators for environmental impact of food – also primarily used by Eaternity), the results of the analyses presented at the meeting in Switzerland showed that the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions per single portion of a meal served ranges somewhere between 200 – 5000 g CO2 equivalents. This is in line with similar studies on carbon footprint of meals found in the literature. The values at the higher end of the range calculated (imagine a beef steak with potato wedges and some veggies or similar) equal to driving a petrol car for about 40 km in the EU[1]. The highest impact comes from meals containing red meat (especially beef, veal and lamb) while meals based on legumes, vegetables and cereals have a much lower carbon footprint. This gets a bit more complicated when different units of the final product are assessed, i.e. the carbon footprint is expressed in energy content (kJ or kcal) or protein content (g) of the ingredients. But in general, animal-based meals tend to group at the higher end, while vegetarian and vegan meals tend to fall into the lower-impact end.

This seems like a fairly clear message that could be communicated to the consumers: Plant-based meals tend to have a lower carbon footprint than meals based on animal products. I use the word ‘tend to’ since this might not work universally for every single meal. Two factors seem to be key here: 1) the amounts of the ingredients used per single portion; and 2) the way of production of the ingredients.

The first point highlights the fact that it makes a big difference if we use for instance 50 g or 200 g of meat or dairy product per single portion of a meal. For this reason it is always good to compare meals that have a similar nutritional value – expressed e.g. in energy content or another nutritional indicator (although it’s subject to a debate what indicators are best at the moment).

The second point relates to the fact that the carbon footprint calculations use average data for the ingredients used in the meals. This is due to the fact that it is currently beyond researchers’ capabilities to calculate impacts for every single farm producing every single food product, the processing factories, the distribution pathways, the waste management etc. etc. along the ingredient’s life cycle. Therefore, the final impact really depends on what kind of produce the consumer chooses to buy. Seasonal? Organic? Processed? Or?

For instance, out-of-season production (in heated greenhouses) or fossil-fuel-intensive transport (e.g. air freight) can make even plant-based meals score very high in climate impact. There are many variations. But research helps in this respect. Most studies conclude that from a carbon footprint perspective:

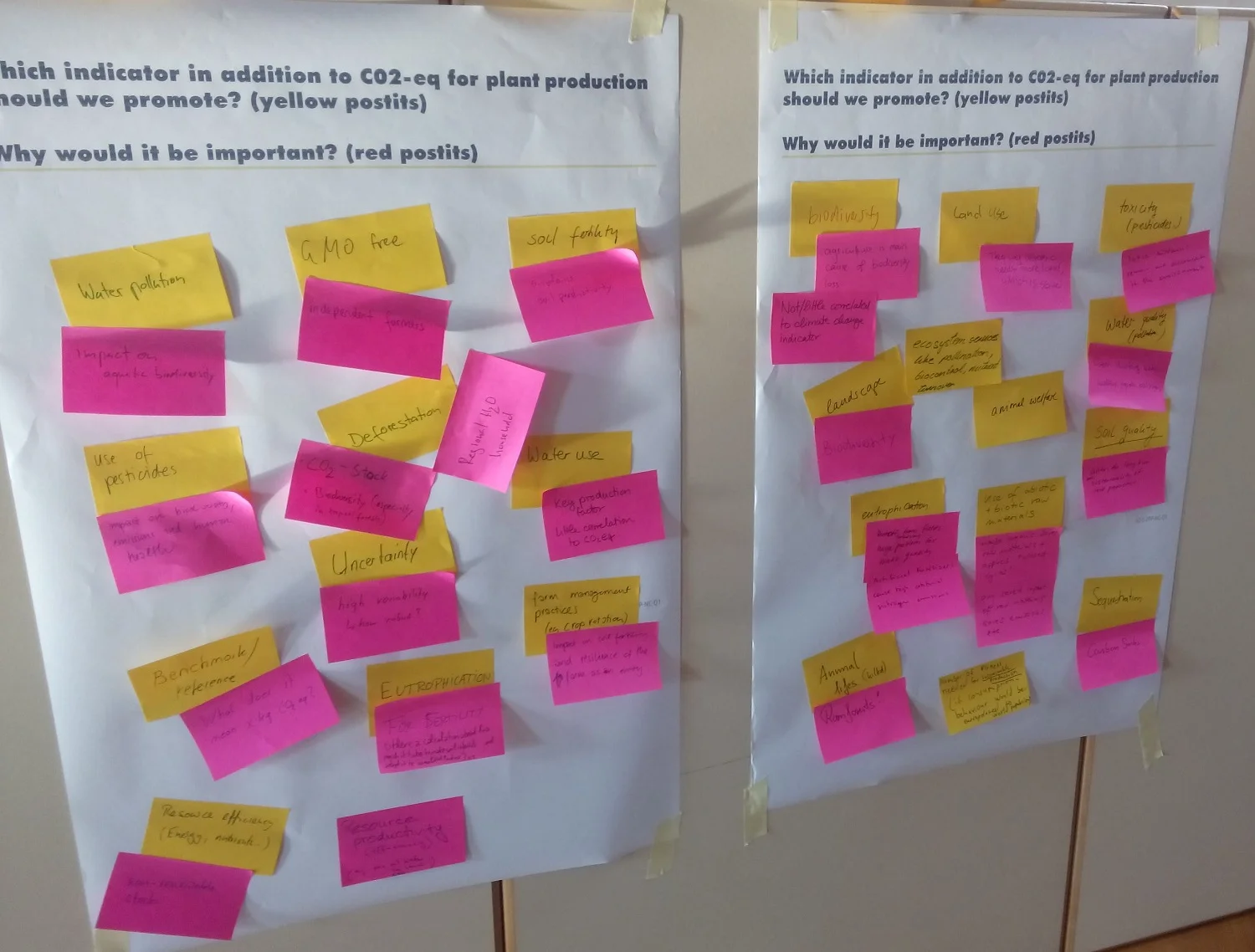

Capturing the knowledge in the room: additional environmental impact indicators to carbon footprint suggested by the workshop participants (photo: Dana Kapitulčinová)

- Seasonal is generally the best option for fruits and vegetables.

- Fresh ingredients (in season) are better than processed.

- Organic produce – not so easy to conclude. Explanation follows!

Are meals cooked from organic ingredients better for the environment than from conventional produce?

Starting with studies on carbon footprint, the answer to this question might come as a surprise: Yes and no! Both results have come out of studies on GHG emissions from organic vs. conventional production and were published in peer-reviewed academic literature. The reason for this difference lies in a number of aspects. For instance, organic production for some crops requires higher use of machinery than conventional production due to the need for weeding of the crop that has not been treated by chemical protection (e.g. pesticides, herbicides). More machinery equals to more diesel which equals to more GHG emissions per kg of final crop in the organic system. But this is not the case universally for all organic farms as there exists large variability between farms (both between certified organic, but also between non-certified “conventional” ones). That’s why we find the different results for organic vs. conventional produce in terms of climate change impacts in the literature.

Also, animal products often come out as worse in the organic system per kg of final product compared with conventional production. This is given by the fact that organically certified animals often live longer in larger living space and therefore use more resources (feed, water, space) and hence produce more GHG emissions. Animal welfare therefore seems to be at odds with ‘environmental efficiency’ here.

Gathering and choosing ideas for future development of environmentally-friendly meals (photo: Dana Kapitulčinová)

So what does that mean for the consumer? Should we recommend abandoning organic produce and animal welfare to lower our environmental impact? Certainly not, we need to be careful not to make early conclusions. What matters most is in fact the total of GHG emissions produced per person in his or her diet over a certain period rather than in one single meal. So if a consumer chooses to eat one organic beef steak once in two months and then eat mostly organic plant-based meals, he/she will have a lower environmental impact than another consumer who chooses to eat beef steak from conventional production once a week. But this does not stop with food of course!

If another consumer gives up eating meat altogether for environmental (or other) reasons, but then chooses to spend all his holidays flying around the world, then the savings of the GHG emissions from the diet will be used up and possibly exceeded by the travel. Therefore, we need to find a good balance in our entire lifestyle regarding GHG emissions. But when I relate this back to my running project in Czechia, one of the key conclusions that I take away from the workshop is that for educational purposes, working with single portions of meals seems to be very useful, since every person can relate to it and imagine replacing it with something else.

Conclusion – further research needed!

So what did I learn during my stay in Zurich? The discussions at the Organic Foodprint workshop indicated that even though organic produce might be intuitively better in many aspects for the environment (such as supporting higher biodiversity, using less toxic chemicals, etc.), it is not exclusively better in all environmental indicators compared to conventional practices. This is true especially in the higher GHG emissions reported in some cases for organic products, which points to the need to come up with innovative solutions to securing renewable fuels and energy for all types of agricultural production. It has been concluded that to assess the environmental sustainability of meals – and food in general – a wide range of key indicators need to be considered and developed further in this field to enable a more holistic assessment. This means that for now we won’t be really able to make an easy distinction between conventional and organic produce in our educational tool in the running project at Charles Univeristy. We’ll simply need to make sure that we keep all the information provided transparent and to inform the users that we all need to be looking forward to more research in this field.

[1] based on the average fuel efficiency of petrol cars (122.6 g CO2 km-1) reported by the European Environment Agency in 2016

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dana Kapitulcinova is a researcher at the Charles University Environment Centre, Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic. She currently leads a 2-year applied research project on meal-based environmental and nutritional accounting – aiming to develop an online educational tool to inform the general public about environmental and nutritional aspects of food consumption (co-funded by the Technological Agency of the Czech Republic). Dana holds a PhD in Environmental Geosciences from the University of Bristol, United Kingdom. She is a WFSC Alumni from the summer school held at Rheinau in 2013.

“The visit to Zurich and the discussions with leading experts there have enriched my understanding of the complexity of environmental footprinting – with a specific focus on meals and organic production. The outcomes will directly feed into my running project as well as future research proposals. I am immensely grateful to the WFSC Ambassadors Program for the financial support that enabled me to share my experience and gain valuable insights in this important research area. Many thanks go to the funder, the WFSC Team, as well as Eaternity for inviting me to join in for the workshops!”